Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has a wonderful talk about “the danger of a single story” that you can listen to, online. When you’re handed the first Hausa-language (spoken in parts of Africa) novel translated into English, you

can get a sense of the perilous burden of that description.In an interesting misrepresentation, the publishers seem to have chosen to promote

this sense of exotic uniqueness, blurbing the book as “quite unlike anything you’ve ever read before”. There is a world of context to be brought to such a claim.Are you familiar with the Indian epics? Then you will be completely at ease with the narrative pausing for a chapter or two to elaborate about the ancestry of its protagonists, with miraculous progeny bestowed on parents yearning for children. Are you used to the materialistic itemization of gifts and assets in chick lit, where millinery detailing stands in for romance? If so, your heart

will delight in all the matter-of-fact lists: gifts given to an illicit lover; gifts given to a first wife upon marriage to a second; gifts given through your parents to the household of your intended. Are you at home in the microcosmic world of an inward-facing society, as portrayed by Jane Austen, or

Enid Blyton, or Shobhaa De? Then you will immediately recognize the insouciant tolerance of the way things are versus the scandal of the things not done (polygamy vs extra-marital affairs, not paying a daughter’s school fees vs not buying her a bed for her marriage).

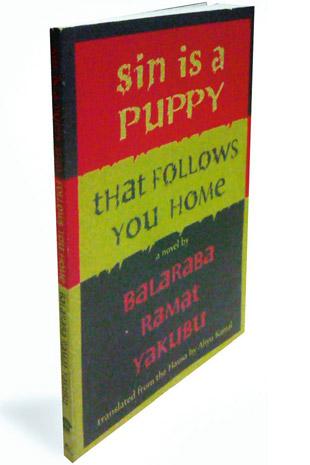

Sin is a Puppy follows the everyday lives of women in

NigeriaSo let us set aside this presumed universalizing “you” who

is being addressed by a Hausa speaker, even as we—Anglophone Indians reading, and writing, this review—acknowledge what this book fulfils. While attempts of Non-Aligned Movement-inspired Afro-Asian solidarity have fizzled in and out of our cultural spheres, we have largely mediated our engagement with Nigerian

writers through the Western-approved, if undeniably great, literary craft practised by Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Ben Okri and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie; Anglophone Igbo and Yoruba writers often expatriated abroad.In terms of cachet, Balaraba Ramat Yakubu is admirably placed, with best-selling author and film-maker credits to her name. Her translator Aliyu Kamal is, in his own right, an English novelist and professor at Bayero University, Nigeria. Blaft has, with great success before, translated popular, mass-market stories and created a literary buzz around them, without undue fetishizing. Let us get the multiple meta-textual reasons for celebrating this book out of the way; it is a Hausa (Muslim, Black, Nigerian, African) woman writing for her peers, made accessible to us by desi publishers who find a glossary to be redundant. Kudos all round!

But what did I actually think about the story of a woman (temporarily) leaving her abusive husband while her daughter finds a suitable boy (or rather, twice married man)?

Sin is a Puppy That Follows You Home: Blaft, 126 pages, Rs 250Dear reader, I was rather charmed by it. Comparing the plot to Ekta Kapoor’s soaps or Karan Johar’s family dramas misrepresents the scale of the story because, for all the theatrics indulged in it, the plot is uncompromisingly stark about how patriarchy, society and religion interfere in women’s desires and autonomy.

I found far more resonances with the pragmatic tragedies of Mahasweta Devi’s stories, or the deceptively mundane female worlds of Ismat Chughtai’s work. Women tear each other down, draw dramatic lines between sluttiness and respectability, rely on brothers and extended family while suffering spousal abuse and abandonment. Romance and courtship are abbreviated to a few

fast-moving dialogues because the author wants to spend time on the minutiae of how a selfish second wife neglects her kitchen duties. Yakubu’s matriarchal lead Rabi—with her culinary enterprise born of desperation, her baffled rage at

her husband’s mistress, her fierce determination to promote her children—is soul sister to Parvati from Kiran Nagarkar’s Ravan and Eddie. Rabi’s daughter Saudatu—dignified, dutiful, happily desirous—resembles Sita in her deference to narrative fiat.The main reason I would recommend reading this book is because of how much it made me feel at home. It is not heartwarming in the treacly manner of popular films, but instead, like the family histories your aunties tell you, full of compromises and small justices, and the “life goes on” approach to domestic tragedy. This is not a story of exotic Africa, nor of epochal moments in histories of colonialism and its aftermath, nor yet about the fetishized tensions of being Muslim. Instead, it is shopkeepers falling in love with women stopping to buy dress material, and mothers vacillating between the street being unsafe and being a good place to meet eligible men, and bored wives

eyeing comely electricians summoned to fix the wiring. Let other books talk about purdah and polygamy; this is a book that concerns itself with soap.

”The truth might be hard to say, painful to bear or even drastic for the truth sayer but still needed to be said”. ALISON.