Chike Nwodo nominated me for the #bookchallenge, which means that for seven consecutive days, I will need to name and say something (briefly) about a book I have read. It is a challenge I have once taken up in the French language and which I enjoyed. So, I have gladly accepted it once more. This time around, I’m reposting (when I judge it necessary) a blog or Facebook post in case I have already written something about the book in the past.

And I started this challenge with 𝕋𝕙𝕖 ℝ𝕚𝕤𝕖 𝕠𝕗 𝕥𝕙𝕖 𝔸𝕗𝕣𝕚𝕔𝕒𝕟 ℕ𝕠𝕧𝕖𝕝: ℙ𝕠𝕝𝕚𝕥𝕚𝕔𝕤 𝕠𝕗 𝕃𝕒𝕟𝕘𝕦𝕒𝕘𝕖, 𝕀𝕕𝕖𝕟𝕥𝕚𝕥𝕪, 𝕒𝕟𝕕 𝕆𝕨𝕟𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕙𝕚𝕡 by 𝕄𝕦𝕜𝕠𝕞𝕒 𝕎𝕒 ℕ𝕘𝕦𝕘𝕚 which changed my perspective on African literature. And yesterday, I presented 𝔸𝕟 𝕆𝕣𝕔𝕙𝕖𝕤𝕥𝕣𝕒 𝕠𝕗 𝕄𝕚𝕟𝕠𝕣𝕚𝕥𝕚𝕖𝕤 𝕠𝕗 ℂ𝕙𝕚𝕘𝕠𝕫𝕚𝕖 𝕆𝕓𝕚𝕠𝕞𝕒 which is a perfect example of what authentic African literature should be: inspired by an African experience or plotted around an Afro setting.

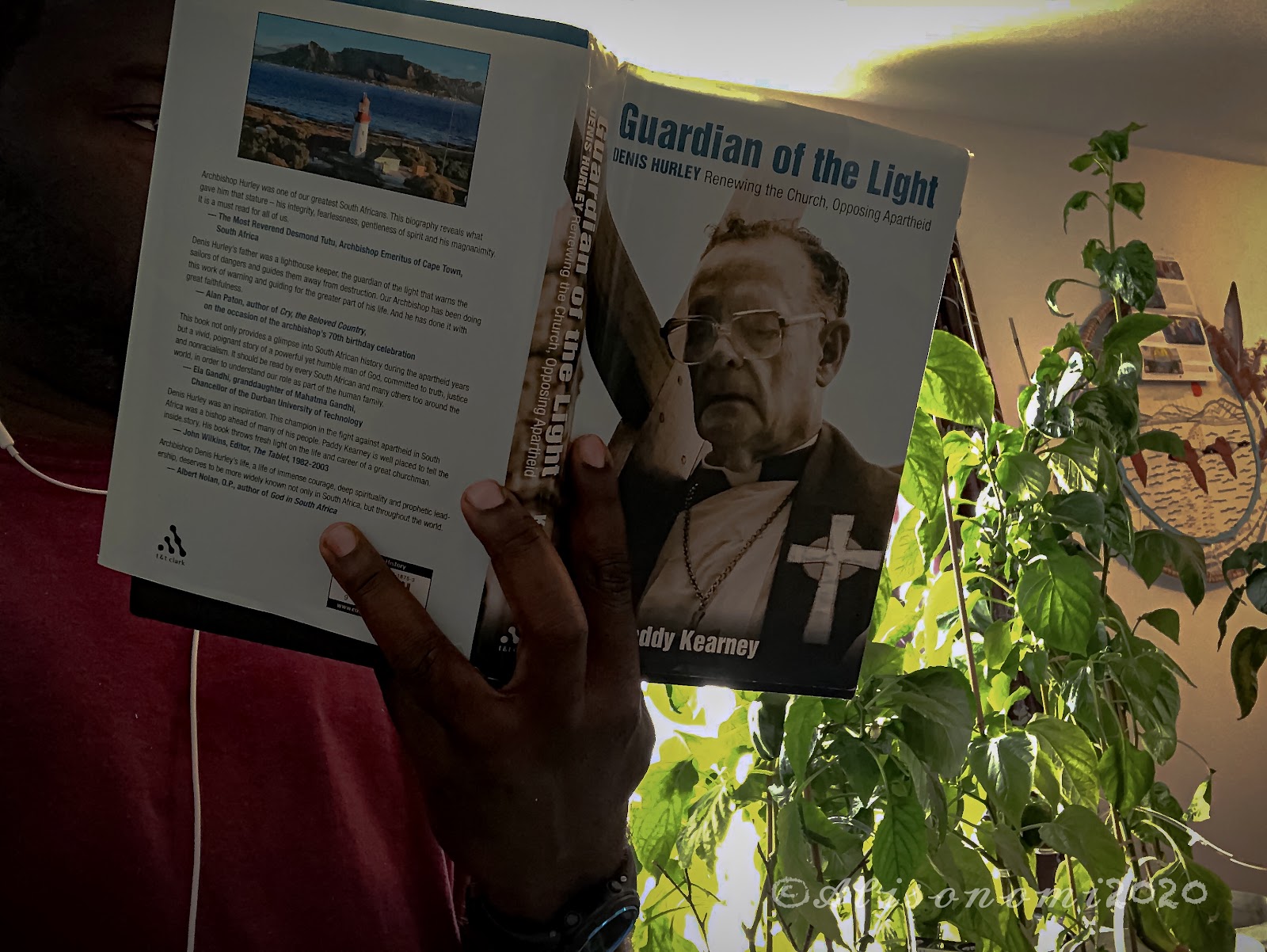

Today, I’m presenting to you a book of a different kind that will help us to continue to explore one of the themes developed by Mukoma. In chapter 5 of 𝕋𝕙𝕖 ℝ𝕚𝕤𝕖 𝕠𝕗 𝕥𝕙𝕖 𝔸𝕗𝕣𝕚𝕔𝕒𝕟 ℕ𝕠𝕧𝕖𝕝, Mukoma made a very important observation on the identity of an African Novel. He underlined that what makes a Novel African is neither the language nor the origin of the writer but mainly the setting of the novel. To buttress this point, I will be presenting to you the 𝔾𝕦𝕒𝕣𝕕𝕚𝕒𝕟 𝕠𝕗 𝕥𝕙𝕖 𝕃𝕚𝕘𝕙𝕥, 𝔻𝔼ℕ𝕀𝕊 ℍ𝕌ℝ𝕃𝔼𝕐: ℝ𝕖𝕟𝕖𝕨𝕚𝕟𝕘 𝕥𝕙𝕖 ℂ𝕙𝕦𝕣𝕔𝕙, 𝕆𝕡𝕡𝕠𝕤𝕚𝕟𝕘 𝔸𝕡𝕒𝕣𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕚𝕕 𝕓𝕪 ℙ𝕒𝕕𝕕𝕪 𝕂𝕖𝕒𝕣𝕟𝕖𝕪.

𝔾𝕦𝕒𝕣𝕕𝕚𝕒𝕟 𝕠𝕗 𝕥𝕙𝕖 𝕃𝕚𝕘𝕙𝕥 is a biography of the South African Archbishop, Denis Hurley, OMI. His Irish father migrated to South Africa at the height of the 1847-50 famine. The parent got married and gave birth to Denis and his other siblings.

The title of the book Guardian of the Light could be taken literally as the father was a lighthouse keeper. But it’s more figurative as the Archbishop ended up becoming a beaming light directing, no longer ships like his father’s lighthouse, but the South African Church to the reality of the indigenous black people of South Africa.

The family first lived in Cape Point and, later, in Robben Island, where very few white residents controlled the most notorious black South African prison (where Madiba was incarcerated for 27 years), a mental hospital, and a leper asylum. Archbishop Hurley had his first contact with the South African racial segregation system in this segregated context and forsaken city.

And, even though the parents gave them every opportunity to thrive in a society where the colour of one’s skin is a key factor to progress and development, Denis would grow up to (𝗽𝗼𝘀𝗶𝘁𝗶𝘃𝗲𝗹𝘆 𝘀𝗽𝗲𝗮𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴), bite the hand that fed him. He had his primary and secondary school staying with (white) Dominican Sisters far from his Godforsaken township. At the end of his secondary education, he joined the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, OMI and was sent to Ireland to pursue his priesthood formation. Denis was later sent to Rome, where he was opportune to witness various faces of the universal Church. Living with other oblates from different parts of the world made him realize the absurdity of a racially segregated society.

And, even though the parents gave them every opportunity to thrive in a society where the colour of one’s skin is a key factor to progress and development, Denis would grow up to (𝗽𝗼𝘀𝗶𝘁𝗶𝘃𝗲𝗹𝘆 𝘀𝗽𝗲𝗮𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴), bite the hand that fed him. He had his primary and secondary school staying with (white) Dominican Sisters far from his Godforsaken township. At the end of his secondary education, he joined the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, OMI and was sent to Ireland to pursue his priesthood formation. Denis was later sent to Rome, where he was opportune to witness various faces of the universal Church. Living with other oblates from different parts of the world made him realize the absurdity of a racially segregated society. On returning to South Africa, he found it difficult to reconcile himself with the way the whites treated the blacks in his native South African society and Church. Young as he was, he tried to identify with the oppressed black and Indian communities, trying to acquaint himself with their realities and finally becoming their very important ally.

Named bishop at the age of 31, he became the world’s youngest bishop. And during the Second Vatican Council II, he would prove to be a force to reckon with as he joined hands with many other prominent bishops who thought that the Church needed to listen more to the afflicted members of society.

And on his return, he pushed for a serious change in the catechetical pedagogy in the South African Church. He promoted the adaptation of the catechism to the local languages of South Africa and worked to improve the social teachings of the South African Church. His efforts as a white South African in the ’60s to make the South African Church closer to the realities of the people is still more progressive than what many black African bishops are doing today. His catechism reform in those years is over 50 years more current than what we observe in many African dioceses today.

There are so many other things that make the biography of Archbishop Hurley a must-read for anybody interested in institutional reform today than can be said in these few lines. According to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, “𝐴𝑟𝑐ℎ𝑏𝑖𝑠ℎ𝑜𝑝 𝐻𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑒𝑦 𝑤𝑎𝑠 𝑜𝑛𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑔𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝑆𝑜𝑢𝑡ℎ 𝐴𝑓𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑛𝑠. 𝑇ℎ𝑖𝑠 𝐵𝑖𝑜𝑔𝑟𝑎𝑝ℎ𝑦 𝑟𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑎𝑙𝑠 𝑤ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑔𝑎𝑣𝑒 ℎ𝑖𝑚 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑒 — ℎ𝑖𝑠 𝑖𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑔𝑟𝑖𝑡𝑦, 𝑓𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑙𝑒𝑠𝑠𝑛𝑒𝑠𝑠, 𝑔𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑠𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑝𝑖𝑟𝑖𝑡 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑀𝑎𝑔𝑛𝑎𝑛𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑡𝑦. 𝐼𝑡 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑚𝑢𝑠𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑑 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑎𝑙𝑙 𝑜𝑓 𝑢𝑠.”

But before I conclude, I have to state that it is not a simple novel, and though beautifully written, it demands a little concentration to appreciate better such a monumental work.

Finally, looking at different moments where the Church kept silent (as many local churches still do today) while the people were being persecuted, one might think that Archbishop Hurley’s experiences have to be promoted to remind the Church of her role as the mother of the afflicted. Also, this biography should serve to remind all the shepherds that they should be the guardian of the light for the people (blacks, natives, immigrants, LGBTQ, etc.) whose condition continues to degenerate today.