On this very day, 17th December 2011, at the Cathedral of Madrid, Spain shall be beatified 22 missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate who were killed during religious persecution in Spain. These twenty-two oblates, priests, scholastics and brothers were martyred alongside another lay catholic just because of their believe in Jesus-Christ. This honour has brought to our dear congregation more members in our heavenly community (to use the expression of the Founder, Saint Eugene de Mazenod).

On this very day, 17th December 2011, at the Cathedral of Madrid, Spain shall be beatified 22 missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate who were killed during religious persecution in Spain. These twenty-two oblates, priests, scholastics and brothers were martyred alongside another lay catholic just because of their believe in Jesus-Christ. This honour has brought to our dear congregation more members in our heavenly community (to use the expression of the Founder, Saint Eugene de Mazenod).

|

|

Some oblate scholastics before the monuments of the Martyrs in Pozuelo

|

Their is, as a matter of fact, something particular about these Martyrs. unlike Blessed Joseph Cebula, omi, who lived and was martyred in Poland, unlike Blessed Joseph Gerard, omi, who spent 60 years of his missionary life in the Basutoland, (Lesotho), these oblate martyrs of Spain are made up oblates of different age and status. In fact, their beatification will be a source of joy, not only for the living oblates but also for the Oblate community in heaven who have, among them the three major groups that make up a perfect oblate community: fathers, brothers and Scholastics. Another reason why the oblate Martyrs of Spain are special is that they been made up oblates of different ages, they will be models for all oblates, young, old, brothers, priest, scholastics, etc.

As we continue to rejoice with the Universal Church, we hope that the courage of these young missionaries will serve as a source of faith to all youths.

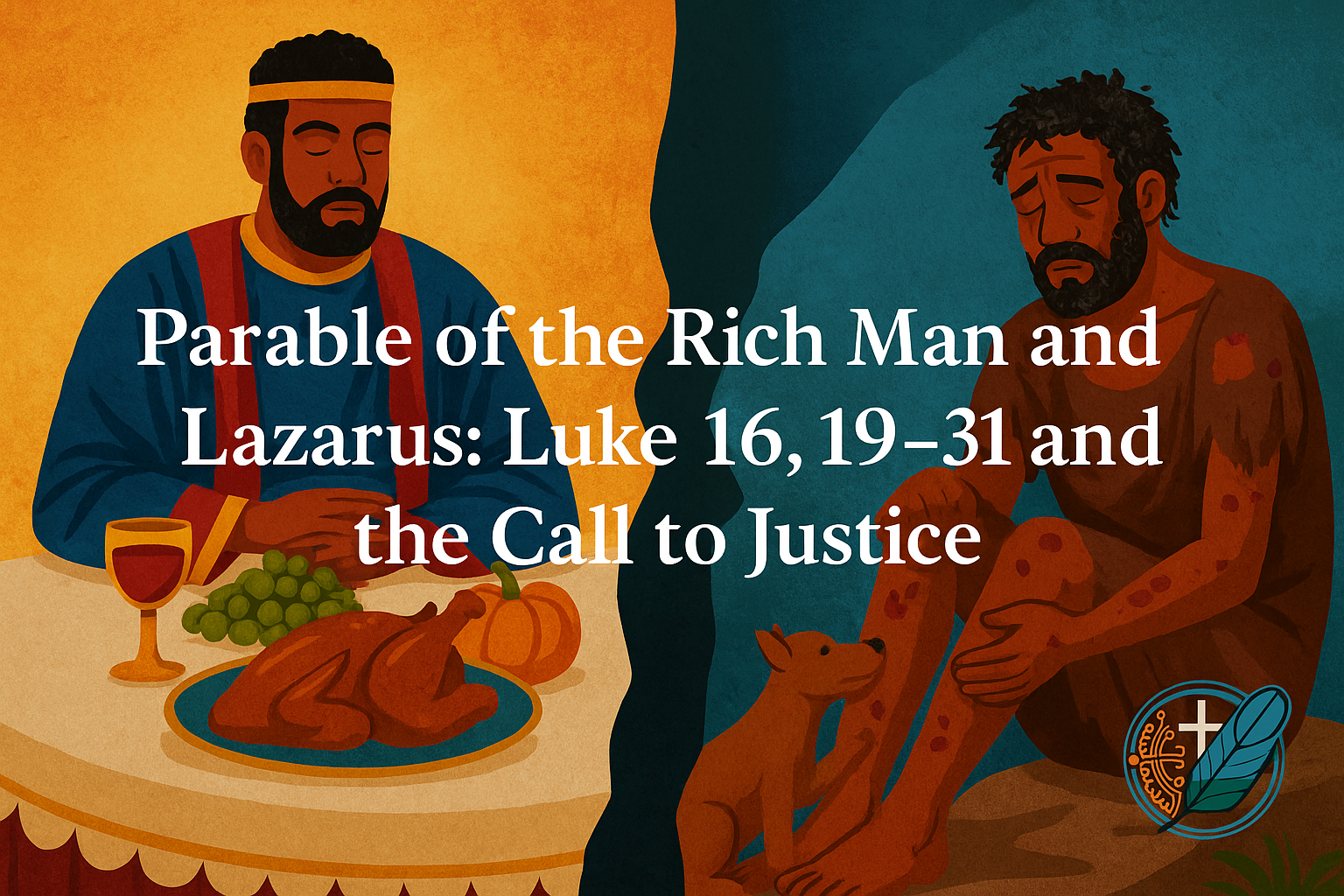

THE STORY OF THE MARTYRS OF POZUELO[1]

Within this general climate of hatred and antireligious fanaticism, one may justly place the martyrdom of 22 Oblates: priests, brothers and scholastics from Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid).

Within this general climate of hatred and antireligious fanaticism, one may justly place the martyrdom of 22 Oblates: priests, brothers and scholastics from Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid).

The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate had established themselves in the Estación neighbourhood of Pozuelo in 1929. They served as chaplains in three communities of sisters. They also provided pastoral service in the surrounding parishes: confessions and preaching, especially during Lent and Holy Week. Oblate scholastics taught catechism in four neighbouring parishes and the Oblate choir sang at liturgical celebrations.

This religious activity began to worry the revolutionary committees (socialists, communists and the radical lay labour unions) in the Estación neighbourhood. They were greatly worried that the “friars” (as they called them) were the driving force behind religious activity in Pozuelo and the surrounding area.

It irritated them that the religious went around in the streets in cassock with the Oblate cross very visible in their cincture.

Within this general climate of hatred and antireligious fanaticism, one may justly place the martyrdom of 22 Oblates: priests, brothers and scholastics from Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid).

Within this general climate of hatred and antireligious fanaticism, one may justly place the martyrdom of 22 Oblates: priests, brothers and scholastics from Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid).The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate had established themselves in the Estación neighbourhood of Pozuelo in 1929. They served as chaplains in three communities of sisters. They also provided pastoral service in the surrounding parishes: confessions and preaching, especially during Lent and Holy Week. Oblate scholastics taught catechism in four neighbouring parishes and the Oblate choir sang at liturgical celebrations.

This religious activity began to worry the revolutionary committees (socialists, communists and the radical lay labour unions) in the Estación neighbourhood. They were greatly worried that the “friars” (as they called them) were the driving force behind religious activity in Pozuelo and the surrounding area.

It irritated them that the religious went around in the streets in cassock with the Oblate cross very visible in their cincture.

Because of these exclusively religious activities, the seminary of the Missionary Oblates was becoming more and more intolerable to these Marxist groups.

The Oblates did not allow themselves be intimidated. They simply adopted an attitude of prudence, composure and calm, committing themselves not to respond to any provocative offense. And of course, none of the religious got mixed up in political activities, not even occasionally. In spite of that, they maintained their program of spiritual and intellectual formation and carried on the various pastoral activities that were part of the priestly and missionary formation of the scholastics.

Even though the demands of the revolutionaries were ever more hostile, the Oblate Superiors could not imagine that things would go as far as they eventually did. It did not even enter their minds that they could be victims of so much hate for their faith in God and for being messengers of Jesus Christ.

On July 20, 1936, socialist and communist youth took to the streets and began again to burn churches and convents, especially in Madrid.

The militia of Pozuelo, on the other hand, attacked the chapel in the Estación neighbourhood; they threw vestments and images into the street and set them afire in a gigantic and sacrilegious orgy. They then burned the chapel and went on to repeat the same scene at the local parish.

On July 22, at three in the afternoon, a large contingent of militia, armed with shotguns and revolvers, attacked the Oblate house. The first thing they did was to round up the religious, some 38 of them, and lock them into a small room where they were closely guarded and threatened by the guns. It was a terribly tense moment because they all thought that they had arrived at the moment of their death. They couldn’t expect anything else, given the edgy, vulgar and chaotic attitude of the militia.

Next, the militia began a meticulous search of the house looking for guns. All that they managed to find were religious pictures, crucifixes, rosaries, and sacred vestments. They threw all of these objects into the stairwell to the lower floor so they could set fire to them in the street.

The Oblates were made prisoners in their own house, brought together in the refectory where the windows were barred. It was their first jail.

On the 24th, at about three in the morning, there were the first executions. Without an inquest, without an indictment, without judgment, without defence, they called out seven of the religious. The first ones sentenced were:

Juan Antonio PÉREZ MAYO, priest and professor, age 29.

Manuel GUTIÉRREZ MARTÍN, scholastic brother and sub-deacon, age 23.

Cecilio VEGA DOMÍNGUEZ, scholastic brother and sub-deacon, age 23.

Juan Pedro COTILLO FERNÁNDEZ, scholastic brother, age 22.

Pascual ALÁEZ MEDINA, scholastic brother, age 19.

Francisco POLVORINOS GÓMEZ, scholastic brother, age 26.

Justo GONZÁLEZ LORENTE, scholastic brother, age 21.

Without any explanation, they were loaded into two cars and taken to their martyrdom. The rest of the religious stayed at the Oblate house and dedicated their waiting hours to prayer and preparing themselves to die well.

Someone, probably the mayor of Pozuelo, informed Madrid of the threat the rest were facing. On that same July 24, a truck arrived from the police with orders to bring the rest of the religious to the General Security Office. On the next day, after filling out some forms, they were unexpectedly let go. They sought refuge in private homes. The provincial put himself at risk by going around to encourage the others and bring them communion. But in October, they were hunted down again, captured and imprisoned in the jail.

There they endured a slow martyrdom of hunger, cold, fear and threats. There are testimonies from some survivors as to how they accepted with heroic patience this difficult situation that implied the possibility of martyrdom. Among them, there reigned a spirit of charity and an atmosphere of silent prayer.

In November, the final moment in that Calvary would come for most of them.

On the 7th, two of them were executed: José VEGA RIAÑO, priest and formator, age 32, and scholastic brother Serviliano RIAÑO HERRERO, age 30, who, when summoned by his executioners, was able to get near the cell of Fr. M. Martin to ask for sacramental absolution

Twenty days later it would be the turn of the 13 others. The procedure would be the same for all. There would be no formal accusation, no judgment, no defence, no explanations: only the calling of their names on powerful loudspeakers.

Francisco ESTEBAN LACAL, Provincial Superior, age 48.

Vicente BLANCO GUADILLA, Local Superior, age 54.

Gregorio ESCOBAR GARCÍA, recently ordained scholastic priest (June 6, 1936), age 24.

Juan José CABALLERO RODRÍGUEZ, scholastic brother and sub-deacon, age 24.

Publio RODRÍGUEZ MOSLARES, scholastic brother, age 24.

Justo GIL PARDO, scholastic brother and deacon, age 26.

Ángel Francisco BOCOS HERNÁNDEZ, coadjutor brother, age 54.

Marcelino SÁNCHEZ FERNÁNDEZ, coadjutor brother, age 26.

José GUERRA ANDRÉS, scholastic brother, age 22.

Daniel GÓMEZ LUCAS, scholastic brother, age 20.

Justo FERNÁNDEZ GONZÁLEZ, scholastic brother, age 18.

Clemente RODRÍGUEZ TEJERINA, scholastic brother, age 18.

Eleuterio PRADO VILLARROEL, coadjutor brother, age 21.

We know that on November 28, 1936, they were taken from the jail, driven to Paracuellos de Jarama and executed there. A scholastic who was in another truck, bound elbow to elbow with Fr. Delfin MONJE, both of whom were mysteriously given a reprieve near the place of execution, said to his companion: “Father, give me general absolution and you pray the act of contrition since the end is near.” The priest, 18 years later, lamented: “It”s too bad I didn’t die then! I would never again be so well prepared!”

It has not been possible to obtain direct information from eyewitnesses about the moment of execution of these 13 Servants of God. Only the gravedigger has declared: “I am completely convinced that on November 28, 1936, a priest or a religious asked the militia if he could say goodbye to all his companions and give them absolution, something he was allowed to do. Once he had finished, he said these words in a loud voice: “We know that you are killing us because we are Catholics and religious. That we are. My companions and I forgive you from the bottom of our hearts. Long live Christ the King!”” There were also members of other religious congregations, but from what this witness has told us, it was the Provincial of the Oblates who said this.

The newly ordained priest, Gregorio Escobar, had written to his family: “I’ve always been deeply touched by the stories of martyrdom that have for all time existed in the Church, and while reading them, I would feel a secret desire to have the same fate as they did. That would be the best sort of priesthood all of us Christians could desire, each of us offering to God our own body and blood as a holocaust for the faith. Wouldn’t it be great to die a martyr!”

It was evident in the diocesan process that all of them died professing the faith and forgiving their tormentors, and that, in spite of the psychological torture during their cruel captivity, none of them denied nor lost the faith, nor did they lament the fact that they had embraced a religious vocation.

For that reason, their family members, their brother Oblates, and the Christian people who know of their fidelity till death, have unanimously considered them martyrs from the very beginning and are praying to God that the Church will recognize them and present them to all the faithful as authentic Christian martyrs.

The Cause for Canonization, for which the diocesan phase ended in Madrid on January 11, 2000, is now in Rome, waiting for a decision from the Holy See to include in the List of Martyrs these 22 Oblate Servants of God.

The Oblates did not allow themselves be intimidated. They simply adopted an attitude of prudence, composure and calm, committing themselves not to respond to any provocative offense. And of course, none of the religious got mixed up in political activities, not even occasionally. In spite of that, they maintained their program of spiritual and intellectual formation and carried on the various pastoral activities that were part of the priestly and missionary formation of the scholastics.

Even though the demands of the revolutionaries were ever more hostile, the Oblate Superiors could not imagine that things would go as far as they eventually did. It did not even enter their minds that they could be victims of so much hate for their faith in God and for being messengers of Jesus Christ.

On July 20, 1936, socialist and communist youth took to the streets and began again to burn churches and convents, especially in Madrid.

The militia of Pozuelo, on the other hand, attacked the chapel in the Estación neighbourhood; they threw vestments and images into the street and set them afire in a gigantic and sacrilegious orgy. They then burned the chapel and went on to repeat the same scene at the local parish.

On July 22, at three in the afternoon, a large contingent of militia, armed with shotguns and revolvers, attacked the Oblate house. The first thing they did was to round up the religious, some 38 of them, and lock them into a small room where they were closely guarded and threatened by the guns. It was a terribly tense moment because they all thought that they had arrived at the moment of their death. They couldn’t expect anything else, given the edgy, vulgar and chaotic attitude of the militia.

Next, the militia began a meticulous search of the house looking for guns. All that they managed to find were religious pictures, crucifixes, rosaries, and sacred vestments. They threw all of these objects into the stairwell to the lower floor so they could set fire to them in the street.

The Oblates were made prisoners in their own house, brought together in the refectory where the windows were barred. It was their first jail.

On the 24th, at about three in the morning, there were the first executions. Without an inquest, without an indictment, without judgment, without defence, they called out seven of the religious. The first ones sentenced were:

Juan Antonio PÉREZ MAYO, priest and professor, age 29.

Manuel GUTIÉRREZ MARTÍN, scholastic brother and sub-deacon, age 23.

Cecilio VEGA DOMÍNGUEZ, scholastic brother and sub-deacon, age 23.

Juan Pedro COTILLO FERNÁNDEZ, scholastic brother, age 22.

Pascual ALÁEZ MEDINA, scholastic brother, age 19.

Francisco POLVORINOS GÓMEZ, scholastic brother, age 26.

Justo GONZÁLEZ LORENTE, scholastic brother, age 21.

Without any explanation, they were loaded into two cars and taken to their martyrdom. The rest of the religious stayed at the Oblate house and dedicated their waiting hours to prayer and preparing themselves to die well.

Someone, probably the mayor of Pozuelo, informed Madrid of the threat the rest were facing. On that same July 24, a truck arrived from the police with orders to bring the rest of the religious to the General Security Office. On the next day, after filling out some forms, they were unexpectedly let go. They sought refuge in private homes. The provincial put himself at risk by going around to encourage the others and bring them communion. But in October, they were hunted down again, captured and imprisoned in the jail.

There they endured a slow martyrdom of hunger, cold, fear and threats. There are testimonies from some survivors as to how they accepted with heroic patience this difficult situation that implied the possibility of martyrdom. Among them, there reigned a spirit of charity and an atmosphere of silent prayer.

In November, the final moment in that Calvary would come for most of them.

On the 7th, two of them were executed: José VEGA RIAÑO, priest and formator, age 32, and scholastic brother Serviliano RIAÑO HERRERO, age 30, who, when summoned by his executioners, was able to get near the cell of Fr. M. Martin to ask for sacramental absolution

Twenty days later it would be the turn of the 13 others. The procedure would be the same for all. There would be no formal accusation, no judgment, no defence, no explanations: only the calling of their names on powerful loudspeakers.

Francisco ESTEBAN LACAL, Provincial Superior, age 48.

Vicente BLANCO GUADILLA, Local Superior, age 54.

Gregorio ESCOBAR GARCÍA, recently ordained scholastic priest (June 6, 1936), age 24.

Juan José CABALLERO RODRÍGUEZ, scholastic brother and sub-deacon, age 24.

Publio RODRÍGUEZ MOSLARES, scholastic brother, age 24.

Justo GIL PARDO, scholastic brother and deacon, age 26.

Ángel Francisco BOCOS HERNÁNDEZ, coadjutor brother, age 54.

Marcelino SÁNCHEZ FERNÁNDEZ, coadjutor brother, age 26.

José GUERRA ANDRÉS, scholastic brother, age 22.

Daniel GÓMEZ LUCAS, scholastic brother, age 20.

Justo FERNÁNDEZ GONZÁLEZ, scholastic brother, age 18.

Clemente RODRÍGUEZ TEJERINA, scholastic brother, age 18.

Eleuterio PRADO VILLARROEL, coadjutor brother, age 21.

We know that on November 28, 1936, they were taken from the jail, driven to Paracuellos de Jarama and executed there. A scholastic who was in another truck, bound elbow to elbow with Fr. Delfin MONJE, both of whom were mysteriously given a reprieve near the place of execution, said to his companion: “Father, give me general absolution and you pray the act of contrition since the end is near.” The priest, 18 years later, lamented: “It”s too bad I didn’t die then! I would never again be so well prepared!”

It has not been possible to obtain direct information from eyewitnesses about the moment of execution of these 13 Servants of God. Only the gravedigger has declared: “I am completely convinced that on November 28, 1936, a priest or a religious asked the militia if he could say goodbye to all his companions and give them absolution, something he was allowed to do. Once he had finished, he said these words in a loud voice: “We know that you are killing us because we are Catholics and religious. That we are. My companions and I forgive you from the bottom of our hearts. Long live Christ the King!”” There were also members of other religious congregations, but from what this witness has told us, it was the Provincial of the Oblates who said this.

The newly ordained priest, Gregorio Escobar, had written to his family: “I’ve always been deeply touched by the stories of martyrdom that have for all time existed in the Church, and while reading them, I would feel a secret desire to have the same fate as they did. That would be the best sort of priesthood all of us Christians could desire, each of us offering to God our own body and blood as a holocaust for the faith. Wouldn’t it be great to die a martyr!”

It was evident in the diocesan process that all of them died professing the faith and forgiving their tormentors, and that, in spite of the psychological torture during their cruel captivity, none of them denied nor lost the faith, nor did they lament the fact that they had embraced a religious vocation.

For that reason, their family members, their brother Oblates, and the Christian people who know of their fidelity till death, have unanimously considered them martyrs from the very beginning and are praying to God that the Church will recognize them and present them to all the faithful as authentic Christian martyrs.

The Cause for Canonization, for which the diocesan phase ended in Madrid on January 11, 2000, is now in Rome, waiting for a decision from the Holy See to include in the List of Martyrs these 22 Oblate Servants of God.